More than 4,300 people have died in the UK after testing positive for coronavirus. Among them are frontline medical staff. Sirin Kale tells the story of two of them.

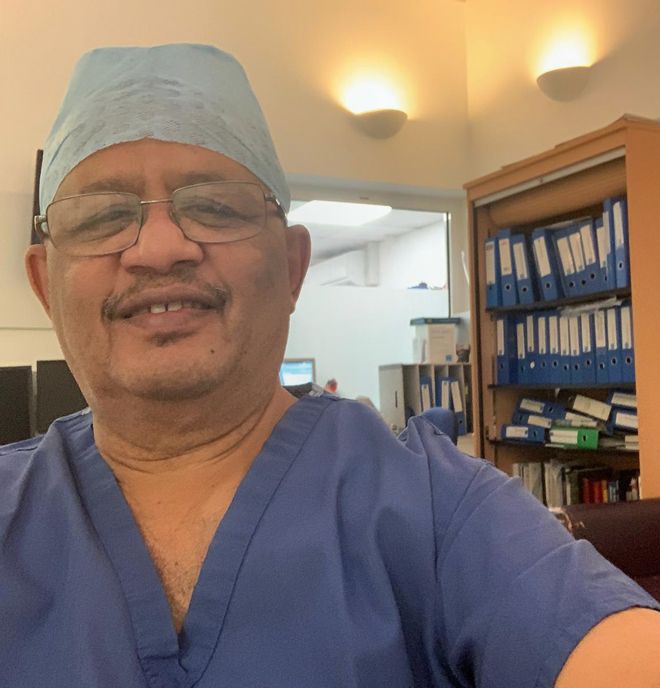

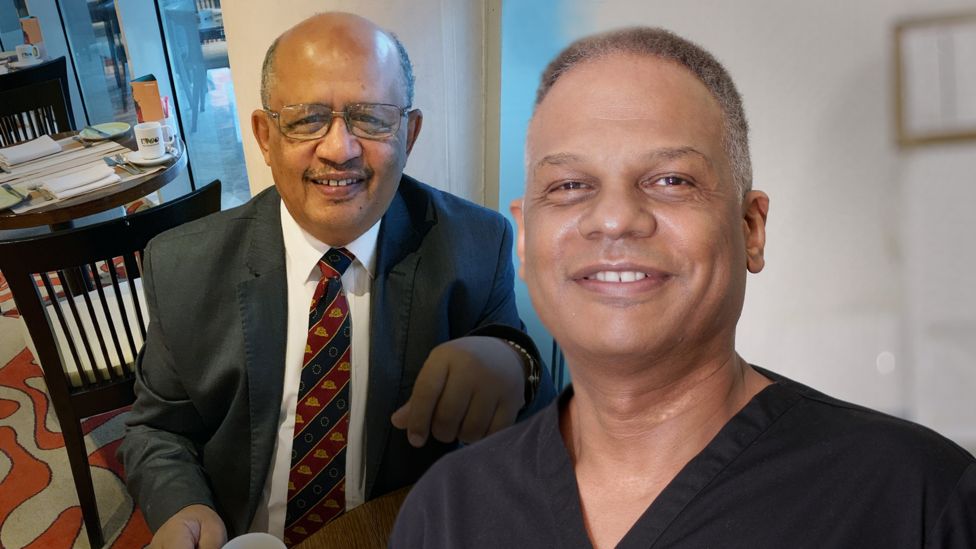

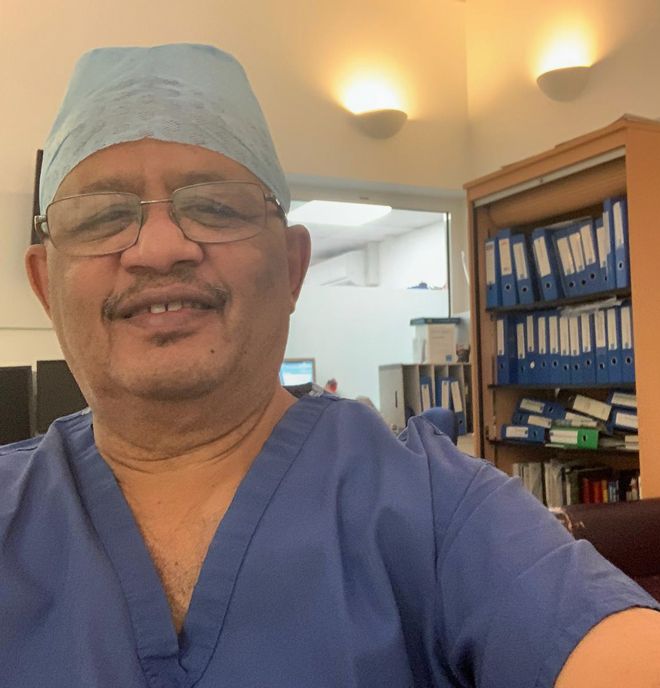

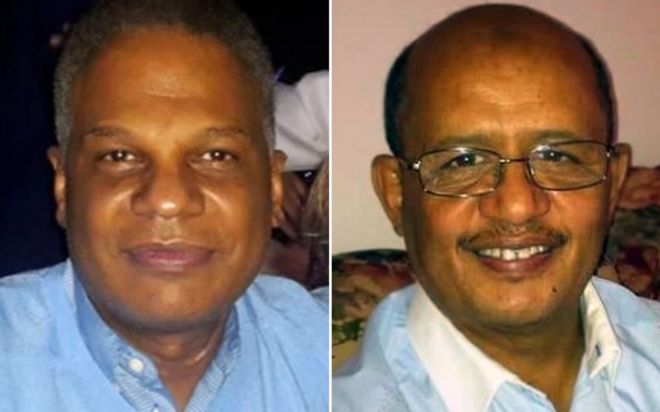

The two men did not know each other, probably their paths never crossed, but in death they would find a strange symmetry. Dr Amged El-Hawrani and Dr Adil El Tayar – two British-Sudanese doctors – became the first working medics to die of coronavirus in the UK.

Their families don’t want them to be remembered in this way – but rather as family men, who loved medicine, helping their community, and their heritage.

Like the many men and women who come from overseas to join the NHS, El-Hawrani, 55, and El Tayar, 64, left behind friends and relatives back home to dedicate their careers to the UK’s health service. They married and had children – El-Hawrani settling in Burton-Upon-Trent; El Tayar in Isleworth, London. And they became pillars of their communities, while maintaining ties to the country of their birth, the Sudan that both men loved.

Their stories are illustrative of the many foreign-born medics who even now are battling Covid-19.

EL TAYAR FAMILY

EL TAYAR FAMILY

Adil El Tayar was born in Atbara in northeast Sudan in 1956, the second of 12 children. His father was a clerk in a government office; his mother had her hands full raising her brood. Atbara was a railway town, built by the British to serve the line between Port Sudan on the Red Sea coast, and Wadi Halfa in the north. It is a close-knit community, where the first Sudanese labour movement started, in 1948. Everyone knows everyone.

“He came from humble beginnings,” says Adil’s cousin, Dr Hisham El Khidir. “Whatever came into that household had to be divided amongst 12 kids. It’s the reason he was so disciplined when he grew up.”

EL TAYAR FAMILY

EL TAYAR FAMILY

In Sudan in the 1950s and 1960s, bright young men became doctors or engineers – respected professions that would give their entire family a better life. And when you’re one of 12 children – well, that’s a lot of people to help look after. Adil knew this, which is why he was a diligent student, even from a young age. But he didn’t mind, in Sudanese culture, looking after your family isn’t seen as a burden. It’s just what you do.

“He was always so serious, so focused,” Hisham remembers. “He wanted to do medicine early on, because it was a good career in a third-world country.” He had a calm, caring disposition. “Never in the years I knew him, did I ever hear him raise his voice.” Hisham looked up to Adil, who was eight years older than him, and later followed in his footsteps to become a doctor.

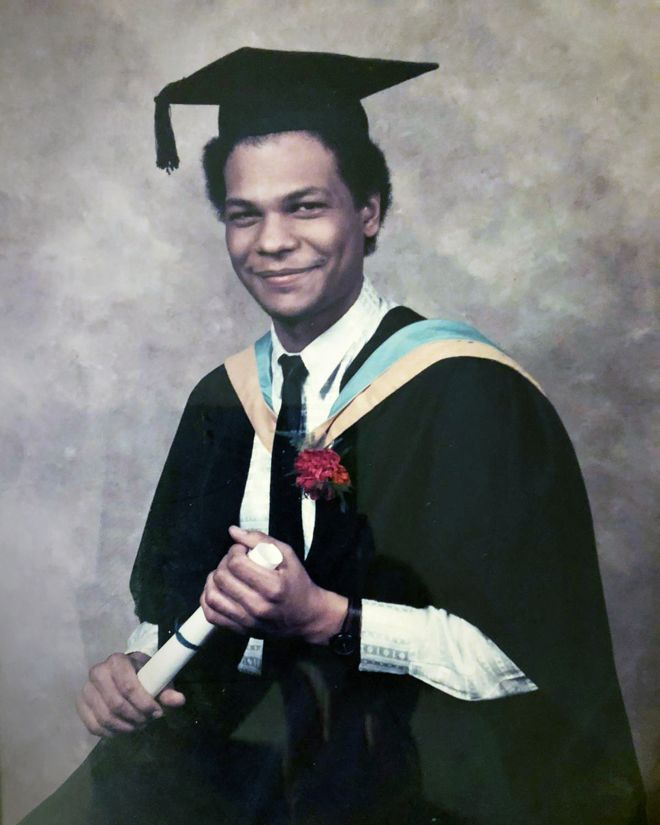

The El-Hawrani family lived almost 350km (217 miles) away, down the single-track railroad that links Atbara to the capital Khartoum. It was there that Amged was born in 1964, the second of six boys. His father Salah was a doctor, and in 1975 the family moved to Taunton, Somerset, before settling in Bristol four years later.

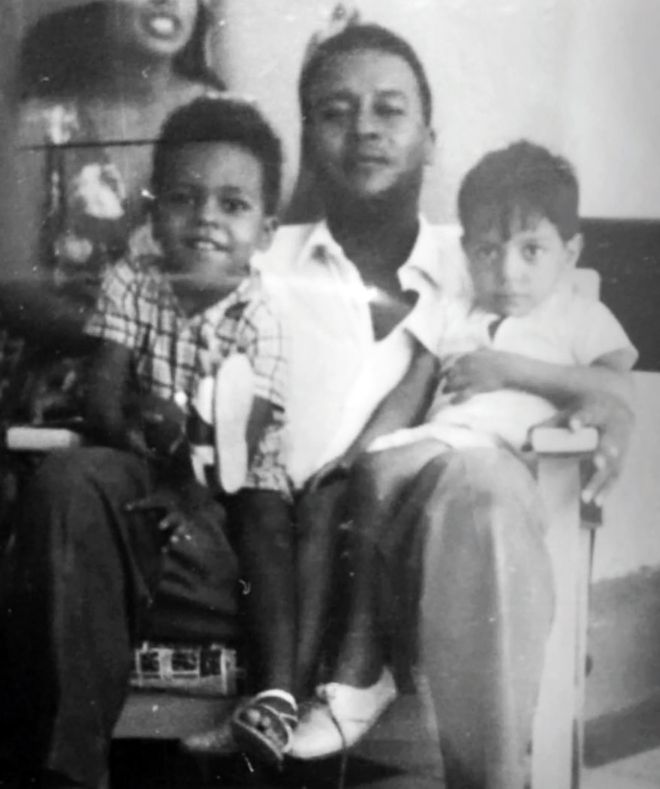

Amged El-Hawrani (left) as a child – with father Salah and older brother Ashraf

Amged El-Hawrani (left) as a child – with father Salah and older brother Ashraf

“Dad was one of the first waves of people coming over from Sudan in the 1970s,” remembers Amged’s younger brother, Amal. “We didn’t know any other Sudanese families growing up in the UK. It was just us and English people. It felt like an adventure. Everything was new and different.”

Only a year apart in age, Amged and his older brother Ashraf were inseparable. “They both could have done anything,” says Amal. “They were intelligent, they were all-rounders. They loved football and technology. They embraced everything – just drank it all in.”

Amged loved gadgets. “He’d always turn up with this bit of kit he’d just bought,” Amal laughs, “saying, ‘Look, I’ve just bought this projector that can fit in your pocket, let’s watch a film!'”

Amged and Ashraf both studied medicine, like their father. And then in 1992, tragedy struck – Ashraf died of an asthma attack, aged 29. It was Amged who discovered his body.

“It had a huge emotional impact on him,” Amal says. “But he became the rock of the family.” He even named his son Ashraf, after his brother.

Over the coming decades, Adil and Amged forged careers in the NHS. Adil become an organ transplant specialist, while Amged specialised in ear, nose, and throat surgery.

The life of an NHS doctor isn’t easy – it is high-stakes work, which often takes you away from your family.

But Adil’s children always felt that he had time for them. “No matter how tired he was, he would always get home from work and make sure he spent time with each of us,” says his daughter Ula, 21. “He cared about family life so much.”

Adil loved to potter about in his garden, tending to his apple and pear trees, and planting flowers all around. “It was his happy place,” says Ula. He also loved to collect new friends. “He’d have barbecues in summer, and there would often be some random person there you’d never met before,” Adil’s son Osman, 30, jokes. “You’d wonder where he’d picked them up from.”

Amged was intellectually curious, and a great conversationalist. “He was one of those people who had an encyclopedic knowledge of everything,” says his brother Amal. He was also a Formula One fan – Ayrton Senna was his legend. “Amged was generous, and without guile,” remembers his friend Dr Simba Oliver Matondo. They met when they took the same class at university, and spent their student years eating Pizza Hut food – a big treat back then – and watching Kung Fu films.

The National Health is staffed by many foreign-born workers – 13.1% of NHS staff say their nationality is not British, and one-in-five come from minority backgrounds.

As of 3 April, four British doctors, and two nurses, have died after testing positive for COVID-19. Five were from BAME [Black, Asian and minority ethnic] communities. In addition to Adil and Amged, there is Dr Alfa Sa’adu, born in Nigeria, Dr Habib Zaidi, born in Pakistan, and nurse Areema Nasreen, who had Pakistani heritage. “We mourn the passing of our colleagues in the fight against Covid-19,” says Dr Salman Waqar of the British Islamic Medical Association. “They enriched our country. Without them, we would not have an NHS.”

‘NHS crown’

- Nurse Aimee O’Rourke, 39, died after a Covid-19 diagnosis on Thursday 2 April.

- On Facebook, her daughter Megan Murphy wrote: “You are an angel and you will wear your NHS crown forever more because you earned that crown the very first day you started.”

- O’Rourke was treated at the Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother Hospital in Margate, Kent, where she worked.

Both Adil and Amged considered themselves British. “Amged was in this country for 40 years,” says Amal. “He was as British as tea and crumpets.” But they kept close ties with their native Sudan. “When someone emigrates to the UK, they don’t just cut all their ties with their country,” Adil’s cousin Hisham explains. “They make a better life for themselves, but they maintain their roots.”

Adil returned to Khartoum in 2010, to set up an organ transplant unit. “He wanted to give something back to the less fortunate in Sudan,” his son Osman explains. Since Adil’s death, his family has received dozens of phone calls from people in Sudan, telling them about their father’s charity work. They knew their dad spent a lot of time helping people back home in Sudan – they’d overhear his phone calls.

But none of Adil’s children realised just how many people he’d helped, until after he died.

Amged was also charitable, climbing in the Himalayas in 2010 to raise money for a CT scanner for Queen’s Hospital Burton, where he worked. Like Adil, he was connected to his heritage. “He’d always reminisce about growing up in Sudan,” says his brother Amal. “He was very proud to be Sudanese.”

His friend Matondo was a frequent visitor at Amged’s mum’s house in Bristol, where they’d eat “ful medames”, a traditional fava bean stew, and feta cheese with chillies. A supporter of Al Merrikh – the Manchester United of Sudan – Amged arranged for the Khartoum team’s dilapidated pitch to be repainted, picking up the bill himself.

Both doctors cared deeply about the NHS, an institution they had spent their lifetimes serving. “Adil really believed in this excellent system that provided free care at the point of delivery to everyone who needed it,” says his cousin Dr Hisham El Khidir.

His passion rubbed off on his children – Osman and his sister Abeer, 26, both followed in Adil’s footsteps to become doctors. The day Osman was accepted as a surgical registrar – a prestigious, competitive post – Adil was emotional. “He was so happy,” Osman remembers. “He just kept saying, ‘Mashallah, mashallah.'”

When both doctors got sick, they didn’t think much of it, their families say. Amged was the first to fall ill. His mother had recently recovered from a nasty bout of pneumonia, and in late February, after finishing a long shift, he drove to Bristol to see her. Amged felt unwell in the car, but assumed he was probably just exhausted.

By 4 March, he was admitted to Burton’s Queen’s Hospital. His colleagues put him on a ventilator. He was later transferred to Glenfield Hospital in Leicester, where he was put on a more sophisticated ECMO machine, to breathe for him. Amged would stay on that machine, fighting for his life, for nearly three weeks.

Meanwhile, Adil was working in the A&E department of Hereford County Hospital. On the 13 March, the first UK death from coronavirus was reported in Scotland. The very next day, Adil started feeling unwell. He came back to the family house in London, and self-isolated.

Over the next few days, his condition deteriorated. On the 20 March, Abeer didn’t like how her dad looked – he was breathless, and couldn’t string a sentence together – and she called an ambulance. Doctors at West Middlesex University Hospital put Adil on a ventilator. But even then, alarm bells weren’t ringing. “We thought, this is bad,” says Osman. “But we had no idea it would be fatal.”

On 25 March, Adil’s family received a call from the hospital. Things were very bad, and they should come now. They raced there to be with him. Adil’s children watched their father die through a glass window. They weren’t allowed in the room, because of the risk of contagion.

“That was the most difficult thing,” says Osman. “Having to watch him. I always knew that one day my father would die. But I thought I would be there, holding his hand. I never imagined I would be looking at him through a window, on a ventilator.”

Adil spent decades serving the NHS. But his family feels that the NHS didn’t do enough for him in return, by giving him the protective gear that might have prevented him contracting coronavirus. “I think it’s unbelievable in the UK in 2020 that we’re battling a life-threatening disease, and our frontline staff are not being safely equipped with PPE to do their job,” says Osman. “Bottom line is that it’s wrong and it needs to be addressed immediately.”

Amid repeated claims of shortages in some parts of the NHS, the government has offered frequent bulletins on the volume of personal protective equipment being delivered. The Health Secretary Matt Hancock has said he will “stop at nothing” to protect frontline health workers – describing the situation as “one of the biggest logistical challenges of peacetime”.

All the time Adil had been in hospital, Amged had clung onto life. But on the 28 March, doctors decided to take Amged off the ECMO machine. Dressed in protective gear, Amged’s brother Akmal was allowed into his room, to hold his hand. Amal watched from behind a window.

Amged will be buried in Bristol, beside his dad, and close enough for his mum to visit.

EL-HAWRANI AND EL TAYAR FAMILIES

EL-HAWRANI AND EL TAYAR FAMILIES

At his own request, Adil will be buried in Sudan, besides his father and grandfather. Getting the repatriation paperwork sorted is proving difficult, given the coronavirus lockdown. “The last wishes of someone who died are very sacred in our culture,” explains Osman. “We will make it happen.”

Adil’s children won’t be able to attend the funeral – although cargo planes are flying, there are currently no passenger flights to Sudan. But he won’t be buried alone. The community of people Adil grew up with – his siblings, and their children, and the people he supported over the years, will bury him instead. In Sudanese tradition, every mourner digs their hand into the dust, and throws soil into the grave. “There are hundreds of people waiting to bury him,” says Osman. “I’ve been on the phone with them all. They’re waiting for him to arrive.”

BBC News